Only four people have driven Sally Miller's incredible rocket-propelled creation, Vanishing Point. Three were pros; the fourth, rookie David Tremayne ...

Zero to 200mph in less than two seconds?

Think about it. At that rate of acceleration, you can cover 10 cricket pitches in less time than it takes a triumphant bowler to yell 'Howzat!'

It seems improbable, impossible. Downright terrifying. Just how do you express what it feels like to attain such a velocity?

Even experienced rocket car drivers such as Sammy, and the late Alan 'Bootsie' Herridge, who've pulled that kind of speed more times than a politician has broken a promise, admit it's a sensation that beggars description.

Somebody once asked Bob Tatroe at Bonneville in 1965 how it felt to drive Walt Arfons' dry rocket-powered Wingfoot Express at 476mph. 'How can you describe how it feels to do 400mph?' he said. 'Someone asks you what chocolate pie tastes like and you tell them it tastes like chocolate. But what does chocolate taste like?'

It's Catch 22. When you've only done it once, you can only really hope to relate fragments of the effect that sort of acceleration has on you, in indistinct hindsight.

Two seconds. Light years less than a billi-second of a lifetime to assess and analyse something beyond the comprehension of most people.

Under a blazing sun, you sit staring straight ahead, heartbeat surprisingly steady. A plane drones overhead like a tired bee seeking a juicy honey plant. Two starlings pull wingovers under the finish lights gantry in the distance, swooping gracefully above the shimmering heat haze. You begin to curse the decision to wear a flameproof facemask. Sammy advised against it because rocket cars don't catch fire. But you knew better. He's only done this a hundred times. Like a wiseguy rookie, you sit and sweat and pay dearly, body temperature already increased by the three-layer Nomex overalls.

Jeez, it's hot in here.

Trish and Sammy move into your vision and lower Vanishing Point's one-piece bodyshell. Their action has a dreadful finality, like the approach of the dentist's needle or the surgeon's knife. You have become cocooned inside a metal and glass-fibre shell from which there is no escape until you have done what you came here to do. The moment you have fretted and fantasised about in equal measures - ever since Mike Greasley walked nonchalantly into the office and uttered the words 'I've got something for you; you're going to accelerate from standstill to 100mph in a second' all those weeks ago - has finally arrived.

Weeks? Brother, it already feels like a lifetime ago. My lifetime.

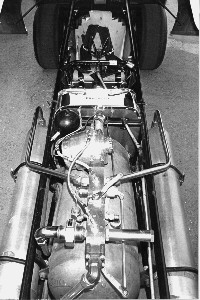

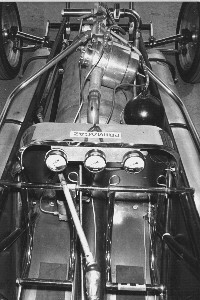

Calm, reassuring and still showing remarkable trust, Sammy kneels down by the open side window, leans in. Pulls back the chrome lever which closes the tank vent. Twists the control down by your knees until the pressure guage reads 50lbs. 'Okay, David. Now just tap the throttle once to get her warmed up.'

You do as you're told and the adrenalin races through your veins faster than lemmings seeking the sea as the rocket behind you belches a sudden, angry roar of impatience.

Christ, do I really want to do this?

Too bad if you don't, boy. You don't have a choice. This is where you find out just how much bottle you've really got. Behind your shoulders the fuse is lit. The clock is running. The hydrogen peroxide is coursing hungrily over the catalyst pack, eager to be separated into its energy creating constituent parts, warming the tiny engine. You purge the rocket again, then Sammy leans through and twirls the pressure way up to 550lbs. There is a glint in his eye as he asks: 'Do you want a real good kick?'

What the hell? What would Bill Muncey have done? Hydroplaning's Mario Andretti told boat owner Willard Rhodes when they shot the propeller-driven water speed record in 1960: 'I'm only gonna do this for you the one time.' He knew fear alright, but he didn't let it get in the way. You feel the same numbing sense of finality Muncey must have. Que sera, sera. But you haven't come all this way to play softball, a misplaced sense of ego tells you. You find your face breaking into a grin, whose weakness is mercifully hidden by the facemask. Maybe it wasn't such a bad idea, after all.

You nod assent and hope it looks eager enough. Got to keep up appearances, old boy.

Just as you realise the folly of such bravado, hands reach over and give your shoulder straps a final tighten. Deist Safety straps. Dear old Jim Deist. Met him in Bonneville in 1981. Big guy. Nice guy. Owns Lee Taylor's old jetboat, Hustler. Didn't try to strap me into a crazy rocket car, but I wouldn't mind running that boat. Seems like a long, long time ago... Anybody know how to turn back the clock?

Sammy is saying something about 200mph. I don't want to know. I thought we were looking at only 100? He moves quietly to the side. 'Just take it easy, David. Relax and keep your head tight into the safety cage.'

He's gone. And you've never felt so alone.

Somewhere outside that plastic cell of loneliness a voice says: 'She's all set. Go when you're ready.'

Your hands grip the steering wheel. Hell, it's not a wheel; it's more like a tiny butterfly. But for the experience it's about to give you, it might as well be a rattlesnake's tail.

Somewhere up that strip of tarmac, your photographer is grinning at you, a Nikon growing out of his face. Nice day for snaps. All of a sudden, photography looks a mighty inviting profession.

Elbows in so hard they hurt as they dig into your rib cage. You've got your head crammed so far back into that goddam rollcage, you'd think your neck is about to snap like a rotten branch. From under your eyelids, you can just see where the track runs. Do you really want to get into this speed game, sucker?

Your own taunt works. Inside you begin to feel a devil stir. A little voice, barely a whisper in the black void, says yes. Unconvincingly. The moment of truth has arrived. God, let anything happen, but please don't let me screw up.

You take a deep breath ...

... and slam your right foot down as far and as hard as it will go.

Two seconds. You'll live them over and again for the rest of your life, letting them loose to roam through the avenues of your mind. Savour them like a fine brandy.

The world ... has gone ... crazy!! Like a ragdoll, your body is slammed back into the seat as a force more powerful than anything you've ever imagined pounds into your back. Behind you, the hydrogen peroxide has separated into water and oxygen and expanded by a factor of 600 at a temperature of 1,340 degrees F. The gases go one way out of the rocket orifice. The car - and you - go in the opposite direction. And you don't go slowly.

The ribbon of tarmac, so still a fraction of a second ago, becomes as distinct as an alcoholic's memories. Marker boards, white lines, light poles - everything on the horizon - blurr and dance in a hazy film as a fearful weight does its best to relocate your head in your lungs. Your eyes can't focus and afterwards someone will tell you gravity is trying to push them round the side of your helmet. An express train has just run into your solar plexus.

That metal and glass-fibre cocoon has been transformed into a vibrant, living monster as the peroxide clamours for escape, slamming you down that drag strip faster than you'll ever travel again on land. Sight, sound, fear, exhilaration - all senses and sensations are obliterated in a remorseless burst of speed that scrambles your brain as effectively as if it has been tossed into the food mixer. You don't know that the rocket's blast has splattered the remote camera tripod set up behind the car the way a sunbather bats away a wasp. You don't even see your photographer as Vanishing Point attacks the horizon. All you care about is holding on, trying to trace a trajectory out of that incredible blur just ahead of the shaking windscreen. It's like every nightmare and every sweet dream you've had rolled into one, so fast that only later will small recollections come back to you, triggered by conversation with others who have shared the thrill.

And all the time - was it really only two itsy bitsy little seconds? - that deafening rocket road assaults your eardrums. Or does it? You're not even sure. Later, you figure it must have, but in the disorientation you can't be certain any more. You don't even cotton on the moment the fuel supply is exhausted, don't realise instantly that the thrust on your spinal column has ceased. Then everything begins to go into slow motion, everything starts to smooth out and the wind pressure begins to act like a giant restraining hand.

But before it begins to pull Vanishing Point back down from its crazy velocity, to something you can understand better, you realise something else.

The steering isn't working! Damn it! The car's veering to the left. Left, left, left. Across the white line dividing the two lanes. From the right where you started, over into the left! Jesus, steer the damn thing! The steering wheel spins uselessly in its column, seemingly remote from the angle of the front wheels. Steer it, damn you!

You think the barrier will hurt as you strike it, speed still around 180mph. It doesn't. Bang! Bang! Jesus, the paint! Not the paint!

Vanishing Point, as if irresistibly drawn to the metal, scrapes and slithers down it. Every impact is agony. Damn any physical concerns, the pain is mental. You've blown it. That beautiful car! Fool!

It goes on for what? 200 yards? There's no fear, that's the funny part. None whatsoever. Even when you know for sure you're going to crash. Goddam it! You blew it. You screwed the pooch! How could you? Gus Grissom where are you?

Gently, very gently, you ease your hand to the brake lever, arrest the final dregs of forward motion. Wait there, in that stifling cockpit, wait for them to let you out. Wait for them to come and see how badly you've hurt that beautiful racer. How are you going to look Sammy in the eye?

The bodywork is raised, propped on its chrome-plated X stand. Helpful hands slacken dear old Jim's belts. Well, they worked, didn't they? You hit the wall at 180 and you didn't feel a thing. You squeeze yourself out of that hotseat with a mixture of relief and reluctance, stepping back into sunlight and sanity. Jeez, that was some ride. Anger fights with the injury to your pride, and the helmet and gloves suffer as they bounce off the ground.

There's a guy standing by your shoulder. Looks like Sammy Miller. Isn't he the guy who makes a living driving these things?

He smiles, but he looks different somehow. In these last few minutes, he's changed, gone far beyond the ordinary human pale. It's already sunk in subconsciously, but now it's coming up for air consciously that you've just had the fastest, most awe-inspiring lesson in respect you'll ever get. Somewhere in the mental jigsaw that is everything the boy and the man ever read, heard and assimilated about record breakers, a few of those missing pieces fall into the right perspectives.

You've been privileged to explore the speed game, to find out a tiny bit about it, but regret keeps impinging on the exhilaration. Why did you screw up?

It's only some time later, after a welcome, throat-slaking coffee (whose effect is immediately negated by an equally necessary cigarette) that the full academic details of the run begin to sink in. Details such as the fact that more than 6,000lbs of thrust were trying to make the seat back part of your ribcage. That an acceleration rate of more than 100mph per second is not far short of what Sammy himself uses. That 550lbs of boost are likewise close to the maximum he employs.

And you did it! You did it, boy. Sat there, calmly, and banged your foot right down. 0 to 247mph in 1.8 seconds! Stayed calm even when you were about to hit the wall. You had your record breaker's moment of truth and passed. But what did you do wrong, goddam it? What else could you possibly have done to keep out of that lousy Armco with its bloody rusty bolts?

It burns you, oh does it ever burn you, but you don't write about it because they ask you not to. Santa Pod always was funny about things like that, sensitive to potential insurance wrangles. You fester for three years, and they let you. Then one day, Roy Phelps finally tells you what really happened.

'You know what they did, don't you?' he asks with a nonchalance that makes you want to grab at him to get it out faster. He must be able to see the look in your eyes. 'Didn't they tell you?' 'Tell me what?' Your voice grates.

'They left the pinch bolt out of the steering column. When you took off, you did what everyone does. You pulled your arms in. Only instead of the bolt holding the steering column in place, it pulled out of its splines. You had no steering right from the start and the wind pressure pushed you over to the left when the power came off. There was nothing you could have done about it.'

Three bloody years! How many nights of soul searching? And they let you go through that, never told you the truth. For a second, you feel an anger like you've never felt before, but then it all comes flooding back, the thrill, the sheer ecstasy of it, only this time, you can savour it properly, without any dark cloud shadowing the background. You can laugh about it now. Hell, it even makes it better.

And this time, when you set your wheels for home, your heart is singing and you think of Blondin, and what he said after he tightroped across Niagara Falls. 'Up there on the wire is living; everything else is just waiting.'

|

|

|

||

| Sponsored by | This site best viewed with Microsoft Internet Explorer 3 | |||